Abstract

Lymphadenopathy is a common presentation in surgical assessment units and has numerous differential diagnoses. In one-stop breast clinics, its discovery often raises concerns of malignancy. This case report focuses on the case of a 33-year-old pregnant woman presenting to the breast clinic with a right axillary lump, which was found to be the result of toxoplasmosis.

Keywords: Congenital toxoplasmosis, Breast cancer, Lymphadenopathy

Background

Lymphadenopathy is a common sign and may present for assessment at any time, including in pregnancy. Its wide differential diagnosis includes inflammatory, infective and neoplastic causes. The most concerning diagnosis is of malignancy, which often predominates the assessment and overshadows rarer causes of lymphadenopathy, including those whose successful treatment is time-critical in pregnancy.

Case history

A 23-week pregnant 33-year-old woman was referred to the one-stop breast clinic for triple assessment, complaining of a 10-week history of a painful right axillary lump. She had no systemic symptoms. She had a past medical history of bilateral benign breast disease and a family history of breast cancer in her maternal grandmother at age 40.

Clinical examination of the left breast and axilla was normal. The right breast showed an indeterminate thickened tissue area at the two o’clock position with associated indeterminate right axillary lymphadenopathy. No other lymphadenopathy was palpable.

Ultrasound of her breasts showed echogenic breast stroma consistent with pregnancy but no focal abnormality. Ultrasound of the right axilla revealed at least two abnormal looking lymph nodes with thickened hila up to 5.8mm (graded indeterminate to suspicious of malignancy U3/4, Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Ultrasound of the right axilla identified at least two abnormal looking lymph nodes with thickened hila up to 5.8mm. This was graded U3/4 (indeterminate to suspicious of malignancy).

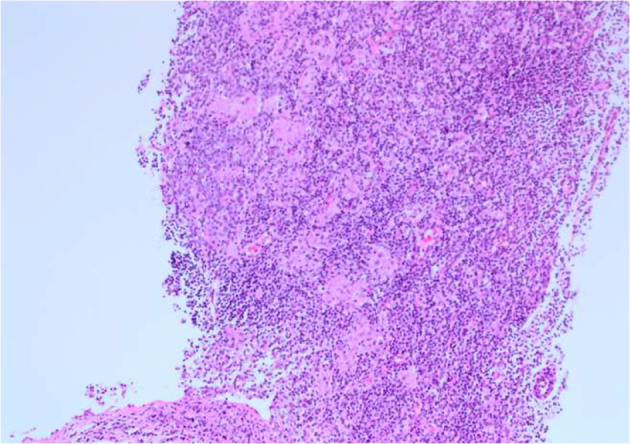

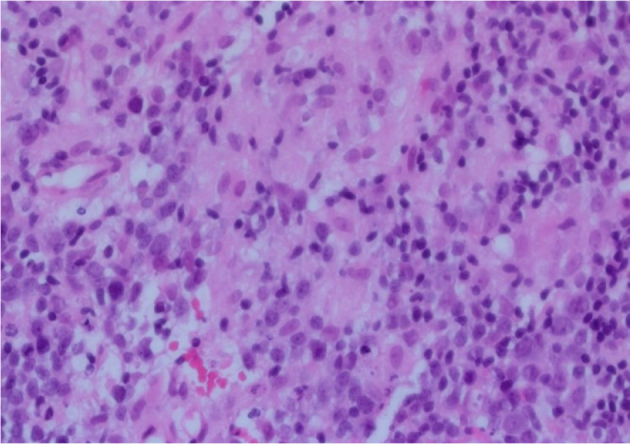

A guided core biopsy of the right axillary node was taken and sent for histological examination. Microscopic examination revealed no evidence of malignancy. The lymph node showed hyperplastic follicles with clusters of epithelioid histiocytes within the germinal centres. The paracortex contained a mixed cell population comprising lymphocytes, plasma and some nucleolated cells, as well as aggregates of pale staining clusters of epithelioid histiocytes (Figures 2 and 3). Immunohistochemical features were of benign reactive lymphadenopathy. The morphological appearances were consistent with reactive lymphadenopathy due to toxoplasmosis, which was confirmed with positive immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies on a blood test.

Figure 2.

Haematoxylin and eosin staining of lymph node core biopsy (× 10 magnification). The paracortex contained a mixed cell population comprising lymphocytes, plasma and some nucleolated cells. Aggregates of pale staining clusters of epithelioid histiocytes can be seen.

Figure 3.

Haematoxylin and eosin staining of lymph node core biopsy (× 40 magnification). The clusters of epithelioid histiocytes are present within the germinal centres.

On direct questioning, the patient did not have any domestic animals. However, she regularly gardened without wearing gloves and she often noticed her neighbour’s cat in her garden. Owing to the risks of congenital transmission, the woman was referred to a specialist centre with experience in infectious diseases.

Fetal growth scans were all normal and invasive investigations for fetal infection were declined. The patient was started on prophylactic treatment with spiramycin and later switched to sulfadiazine/pyrimethamine and folinic acid to prevent vertical transmission of toxoplasmosis. The patient had a normal vaginal delivery at 42 weeks and all newborn postnatal investigations have been normal.

Discussion

Lymphadenopathy is a common clinical sign in surgical outpatient clinics. Concerns of malignancy usually dominate the assessment, but its wide differential diagnosis makes it particularly difficult to consider rarer causes such as toxoplasmosis. Delayed diagnosis may lead to missing the critical time period for intervention, leading to severe complications for fetuses and neonates.

Toxoplasmosis is a parasitic infection caused by Toxoplasma gondii. The definitive hosts of T. gondii are the cat family but it can also infect birds, rodents and animals bred for human consumption.1 Approximately 25–30% of the world’s human population is infected but this number varies greatly within and between countries, with highest prevalence found in Latin America and tropical African countries.2 Over 80% of immunocompetent subjects in European and North American countries are asymptomatic during primary infection.2 The remaining cases may complain of tender lymph nodes and flu-like symptoms.

Toxoplasmosis is diagnosed by serology – a positive IgG indicates prior exposure (but may be negative in immunocompromised patients); negative IgM excludes acute infection but positive IgM may not indicate acute infection as it can remain detectable for one year or longer.2 Pregnant women can have IgG avidity testing or the differential agglutination (AC/HS) test as part of a test panel to exclude acute infection.2,4

Humans become infected via consumption of tissue cysts in poorly prepared meat or via contact with environmental samples (eg soil) contaminated with the faeces of infected cats.1,2 Vertical transmission is another important route to be aware of. Vertical transmission usually occurs during primary infection in pregnancy, leading to congenital toxoplasmosis.3 The birth prevalence of congenital toxoplasmosis ranges from 1 to 10 / 10,000 livebirths.4 Currently, there is no antenatal screening programme for toxoplasmosis infection, however a retrospective study in Austria suggested prenatal screening may be cost effective.5

Fetal transmission depends on the gestational age at which maternal primary infection occurs – transmission rate ranges from 25% in the first trimester to 65% in the third trimester.1 The clinical severity of the disease also depends on gestational age such that early transmission results in more severe manifestations.2,4

Fetal infection may result in spontaneous abortion, prematurity or stillbirth.1 Congenital toxoplasmosis is subclinical in 75% of infected newborns and may be mistaken for other diseases.1,4 If clinically apparent, then central nervous system complications such as chorioretinitis, intracranial calcifications and hydrocephalus are characteristic.1 In the absence of any obvious signs of infection at birth, 14–85% of newborns will develop signs and symptoms months to years later, including chorioretinitis, deafness and developmental delay.1

Pregnant women are advised to avoid eating unwashed vegetables and fruits, and raw meat, and to avoid contact with cats and any activities that expose them to cat faeces.1

The incidence of vertical transmission may be reduced by 60% through the use of spiramycin.4 Pyrimethamine/sulfonamide with folinic acid may also be used after the first trimester of pregnancy.2

Fetal infection is confirmed by positive polymerase chain reaction results of amniotic fluid. Treatment consists of pyrimethamine/sulfonamide with folinic acid, which reduces the sequelae among infected infants.4

Conclusion

Congenital toxoplasmosis is a severely disabling disease. It is important to identify maternal toxoplasmosis promptly to allow early intervention and prevention. Owing to its non-specific presentation, infection may mimic other medical conditions such as breast cancer or lymphoma. Awareness of its clinical presentation among medical and surgical professionals will allow prompt diagnosis, and an appropriate and timely course of action to prevent severe complications for vulnerable groups such as fetuses.

Acknowledgements

This case was presented at the 39th Congress of the European Society of Surgical Oncology in Rotterdam, Netherlands, 9–11 October 2019.

References

- 1.McAuley JB. Congenital toxoplasmosis. J Pediatr Infects Dis Soc 2014; : S30–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert-Gangneux F, Dardé ML. Epidemiology of and diagnostic strategies for toxoplasmosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012; : 264–296. (Correction. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012; 25: 583.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindsay DS, Dubey JP. Toxoplasma gondii: the changing paradigm of congenital toxoplasmosis. Parasitology [Online]. 2011; : 1829–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 2004; : 1965–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prusa AR, Kasper DC, Sawers L et al. . Congenital toxoplasmosis in Austria: prenatal screening for prevention is cost-saving. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017; : e0005648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

.webp)